A Culture of Care

Rewilding Worldings

The assassination of African Americans, indigenous social leaders, and environmental activists is not unique to our particular moment. Instead, they are part of the perpetuation of a system of violence that has been rendered hegemonic as the only legitimate way of being and existing in the world. A world made through the oppression, condemnation, and extinction of the human and other-than-human other. Given that the imminent persecution and killing of people of color worldwide makes visible the deep-seated colonial and neoliberal logic, we must assume this state of exception as having to do with the broader extractivist rationale that orders and gives sense to a modern-colonial world logic. A rationale that today not only needs to be radically disarticulated but that also urgently necessitates frameworks and methodologies that can help yield new paradigms for re-existence.

That is why, in the face of the multiple (and multiplying) forms of extinction, we must elaborate on ways of repair that account for a post-human and multiple-species justice. In other words, types of collective rewilding that can help us institute a culture of care. This “culture” however, requires that we address the multi-systemic crises with an awareness of the ways in which different people are experiencing the state of exception, so as to insist on the urgent need to incorporate intersectional modes of solidarity.

In accordance with contemporary indigenous ecocriticism, this approach stems from the understanding that environmental destruction is one of the larger systems that uphold colonial domination. Seeking both the preservation of our multiple and heterogeneous ecosystems, and the deterrence of growing climate violence, the notion of care through rewilding that is suggested here is also one closely intertwined with the past. A pastness that altogether accounts for the varied histories of colonialism, the acknowledgment of subsumed forms of resilience and resistance, and the uplifting of testimonies of survival that can lead us, following Donna Haraway, towards a multi-species flourishing.

More so than a declaration, this proposition for collective rewilding is an invitation for our readers to join us in researching, experimenting, and implementing a culture of care in the arts and beyond. In that sense, we invite you to think with us in asking: "How do we curate for a broken world?"

a case against inclusion?

Faced with a dawning ecological catastrophe climate change discourse has seen increasing calls for multicultural inclusion – the inclusion of alternative epistemologies, ways of seeing the world, co-living, and ecological and ontological frameworks. And rightly so: the voices of minorities have been ignored and their knowledge devalued for centuries of colonization leading to an exclusively Western discourse around an exclusively Western-made problem.

Similarly, exhibitions showing Indigenous art – specifically works on nature and the environment – have been appearing in Western art institutions for some time now. However, despite this current trend, the sudden interest of Western curatorial practice to “include” Indigenous art, its ecologies, and ontologies is not talked about enough. Instead of being critically analyzed, exhibitions featuring Indigenous art are praised for their progressiveness in diverting focus from Western artistic production. What is quick to be labeled “inclusive” curation, tends to disguise the appropriative, center-peripheral colonial frameworks that the very practice of art curation is still entrenched in.

Podcast hosted by Maja Renfer for BA Culture, Criticism and Curation at Central Saint Martins in conversation with Ameli M. Klein and Sara Garzón from Collective Rewilding.

CARE MEANS ACCOUNTABILITY

Following Patricia Reed thinking to care means explicitly to develop systems and practices of accountability. That is, providing systems of love and care to humans and other than humans in order to guarantee that everyone is being accounted for. It also means that we become responsible for the damage caused directly or indirectly to others, for we are part of the larger forces that uphold inequality, violence, and destruction. In that sense, to care is to provide new imaginaries and narratives for other ways of worldmaking. Alternative practices of the real that help us be and exist in the world differently.

To actually institute a culture of care, moreover, we need to subject institutions to a radical transformation and develop holistic and multi-systemic answers to living in a world in crisis. Mass tourism, carbon footprint, workers’ rights, social precarization, and cultural practices that uphold colonialism and white supremacy are some of the many issues that artistic institutions need to vet today to become sites for rewilding.

The concept of Rewilding emerges in the early 1990s preservation discussions and is first introduced by the environmentalist Dave Foreman. He uses the term to talk about wilderness restoration of native species and processes. The term is still predominantly used in an environmental context and has multiple connotations that usually share a long term aim of restoring and maintaining wilderness while reducing the past, present, or future impact of humans on nature. The process implies returning “non-wild” cultivated areas back to a “wild” natural state. (In a sense reversing the anthropocene). The term rewilding is problematic for it evokes a romanticized ideology of the “wild” as it is often fetishized from a historical, eurocentric perspective. It also seemingly implies a rivalry of wilderness vs. culture, re-rooting culture as progress and nature as an idealized, permanent yet terminated state that is somehow positioned in the past or the exotic faraway. However, we are very interested in the possibilities of the term as it allows the implication that humans have a responsibility to other human or non-human species to restore self-regulating and self-sustaining ecological communities. It is, however, unimaginable to think rewilding without considering the social, cultural, psychological, economic, and political dimensions of its process. Repositioning humans as a part of nature and the wild, instead of its conqueror dominating its surroundings to the will of progress.

We are therefore thinking with the term as a possibility to question art institutional practices, to deconstruct the very foundation of “culture” as a man made superior model, and to acknowledge the importance of holistic natural systems as an alternative form to structure the institution. Rewilding for us means understanding our responsibilities, our relationship with nature, and other peoples as well as getting insights that can inform adaptive management and sustainable development of artistic projects.

The debate on the sustainability of art institutions within the current economic panorama has also occurred at the same time that social protesting has been actively taking down colonial monuments for these continue to uphold white supremacy and racism across the world. In fact, the present crisis of art institutions is not only symptomatic of the current economic situation but has emerged because, as repositories of colonialism’s history, some institutions are no different from those very monuments that today naturalize the perpetuation of oppressive regimes.

By inquiring into the intertwined role of monuments and colonialism, we bring to bear the fact that museum collections are not neutral places of representation. That is why it is essential that we no longer believe in the museum as a place where one can allegedly have a disinterested conversation about race, violence, climate change, or colonialism, but to realize that institutions are equally entangled in perpetuating those same ideologies. In light of this critical discussion on biennial and museums' future that has raised art institutions’ (in)capacity to foreground care, curator Yesomi Umolu's "14 points of the limits of knowledge and care" provides an essential perspective in the ironic relationship between caring for cultural heritage and patrimony, while neglecting the people, communities and environments they represent. The list elucidates museums' claim to care for cultural heritage despite their lack of neutrality in terms of representation, inclusion, and critical interrogation of their history as social and educational institutions.

14 points of the limits of knowledge and care

Yesomi Umolu

Museums are built on the ideological foundations of being repositories of knowledge and spaces of care in service of civic society in the western world.

The history of museums is tied to the colonial impulse to collect and amass objects and, therefore, cultural knowledge from the world over, charging specialists, caretakers/scientists with their interpretation.

The conditions of collecting upon which museums were founded are inextricably linked to colonial violence enacted on the other -non-western bodies, spaces, and societies.

Museums have obscured this violence in their mission of knowledge formation and caring objects.

Care in museums has expanded from a focus on safeguarding things and building western art history in the 19th century to the reification of public engagement in the 21st century.

Museums have always been exclusionary and for the privileged. They were built for the betterment of the western subject and society at the expense of the other.

This is further complicated by the fiction of the emancipatory power of the cultural/art object-museums are deemed to be spaces of respite away from real politics and societal justices.

Museums have therefore set themselves in a double bind, presuming to be at the service of civic society on the one hand while setting themselves apart from It on the other hand.

If museums amass knowledge and care for things, then the question that has been provoked in the midst of the social upheavals and global health pandemic of recent days, months, and years is: for whom do they do this?

The answer is obvious. The statements from museum leaders in recent and coming days starkly reveal this. To acknowledge the limits of your knowing and caretaking is an important step.

But to seek to make amends repair, reconcile and build for the future on broken foundations is a difficult and potentially dangerous path.

The task of the moment is not to seek to welcome the other and the excluded into these fragile spaces i.e. filling quotas and exacting hastened inclusion policies. For the violence will only be worsened.

The task is to commit to practices of knowing and care that critically interrogate the fraught history of museums and their contemporary form, uprooting weak foundations and re-rooting upon new, healthy ones.

Let us know and care for the other, ourselves, and society-at-large in equal measure, without prejudice. Let us know and care about bodies and their politics.

On making curation a rewilding practice

Sara Garzon in conversation with Sebastian Cichocki on the meaning and potentialities of "rewilding." In the talk the speakers discuss Collective Rewilding's larger question: how can we make curation a rewilding practice?

Sebastian Cichocki lives and works in Warsaw, where he is the chief curator at the Museum of Modern Art. Selected curated exhibitions include the most recent "The Penumbral Age. Art in the Time of Planetary Change" (2020) at Warsaw Museum of Modern Art; the Polish pavilions at the 52nd and 54th Venice Biennales, with Monika Sosnowska (1:1) and Yael Bartana (... and Europe will Be Stunned) respectively, the latter project co-curated with Galit Eilat, Making Use. Life in Postartistic Times, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2016), Rainbow in the Dark: On the Joy and Torment of Faith, Konstmuseum Malmö (2015), SALT Galata, Istanbul (2014), Zofia Rydet, Record 1978-1990, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2015), Procedures for the Head, Kunsthalle Bratislava, Slovakia (2015), New National Art. National Realism in the XXIth Poland Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2012), Early Years, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2010), Raqs Media Collective, The Capital of Accumulation, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2010), Oskar Hansen. Process and Art 1966-2005, Museum of Modern Art in Skopje, Macedonia. Cichocki is a curator of The Bródno Sculpture Park, a long-term public art programme initiated in 2009 with the artist Paweł Althamer. He has curated exhibitions in the form of a novella, radio drama, opera libretto, garden, anti-production residency programme, and performance lectures.

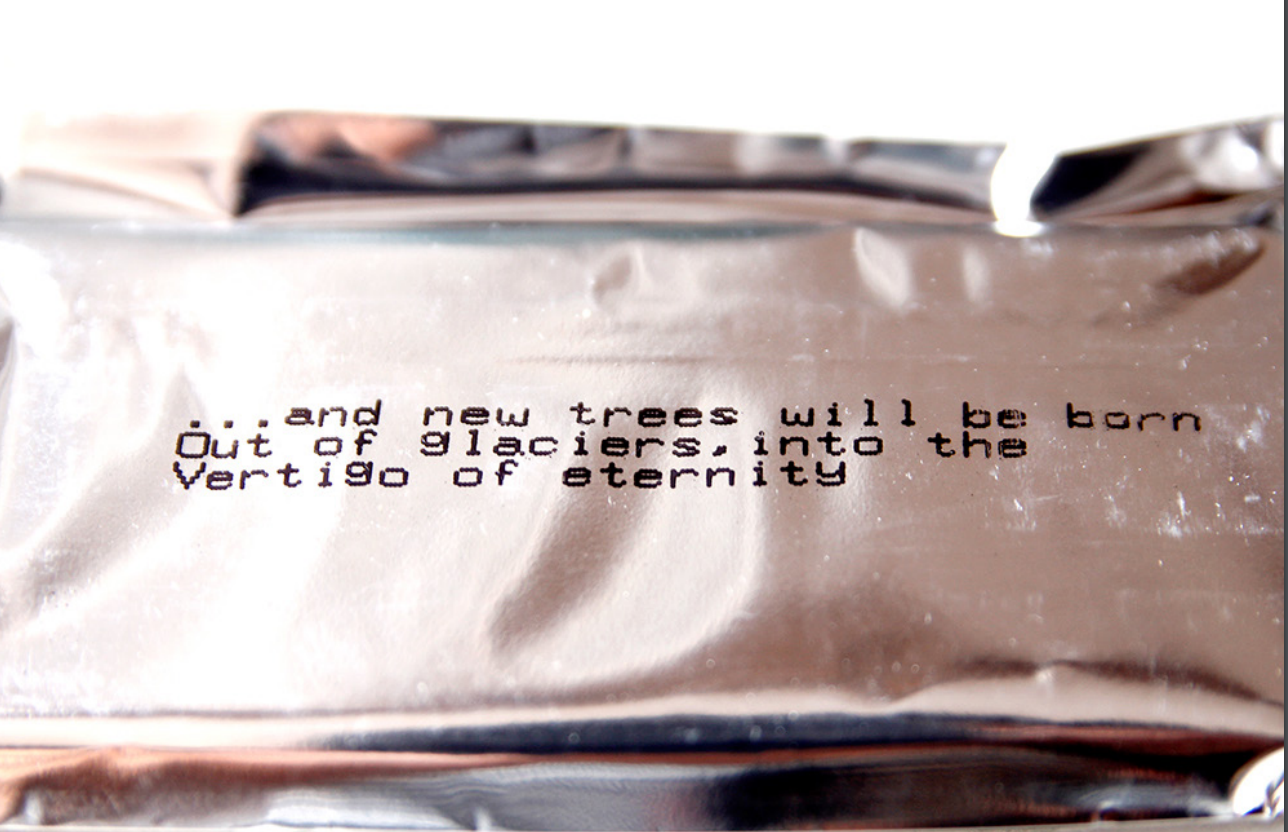

Sebastian shared some of the images from his recent exhibition "The Penumbral Age" that speak directly to the question of rewilding as a curatorial practice.

“What I see now is that human civilization is in the process of trying to become like Earth, in the sense of learning how to become a persistent system. In this century, we’re going to get a lot of harsh lessons on how not to persist — and then we will either correct that, or we won’t.”

— Stewart Brand, writer and editor of the Whole Earth Catalog and of CoEvolution Quarterly

The Planthropocene: The Age of Plants and Plant Creativity

What is the Plantropocene and how can we become more attuned to notions of plant creativity, perception, and worldmaking capacities? This is one of a two part series on plant intelligence intended to help us inquire into how to curate for a broken world by providing spaces for interspecies flourishing?

The conversation follows Paul’s text “The Revolution Will Launch in the Garden; Politics of representation and vegetal intellig(senti)ence” published at Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros’ online platform last year.

Paul Rosero Contreras (Quito, 1982) is a multimedia artist working with speculative realism, scientific information and fictional narratives. His body of work intertwines distinct epistemologies, ranging from indigenous thinking to the history of science. It explores topics related to geopolitics, interspecies reciprocity, environmental issues and experimentation on future sustainable settings. Rosero holds an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts – CalArts and a Master in Cognitive Systems and Interactive Media from Universidad Pompeu Fabra, Spain. His work has received different prizes and grants, and it has been displayed widely at venues and events such as the 57th Venice Biennale, Musee Quai Branly in Paris, Instituto Cervantes in Rome, Museo de Historia de Zaragoza, 5th Moscow Biennale for Young Art, the 1st. Antarctic Biennale, H2 Center, Augsburg, 11th. Cuenca Biennale, 1st. Bienal Sur in Buenos Aires, at Siggraph in Los Angeles, among other spaces. Currently, Rosero teaches and conducts research at San Francisco de Quito University.