As an exploratory site for researching this impetus for Cur(at)ing for a Broken World, we have taken up mass tourism to further unpack the many paradoxes and complexities faced by the environmental crisis and its relationship with the global artistic community. Tourism, especially artistic tourism, partakes in the perpetuation of climate violence around the world. We inquired into the notion of the tourist as a spectator who, often seen as a passive viewer, is, in actuality, an active contributor to the precarization of many communities around the world. With that perspective, we wanted to challenge the common practice of art tourism and the tourist at large so that through a revision of our relationship to territory, we can establish new ways of occupying (as guests) a particular place and community. For this, we have taken up a few case studies to help interrogate tourism as a practice that underscores an extractivist relationship whereby communities get displaced and diminished while the environment gets equally threatened.

In his book "Tourism as an Index Fossil of Modernity—Continuity and Change," German historian and sociologist Hasso Spode states that: "Index fossils are ossified remains that allow geologists to identify the boundaries of different geological strata. In cultural history, tourism is such an indicator for modernity." Spode, moreover, focuses on the ambivalence of this development. He explains that mass tourism hs signified the democratization of elite practices bringing affluence to impoverished regions such as the Alps or Europe's coasts. Here the tourist gaze has managed to transform places that had previously been considered ugly into "authentic" and "natural" attractions. On the other hand, the tourism industry has always posed a cultural and physical threat to those very places through the sheer mass of visitors brought by large scale cruise ships, tourist buses, and vacation packages that have substantial impacts on nature and these communities’ ecosystems.

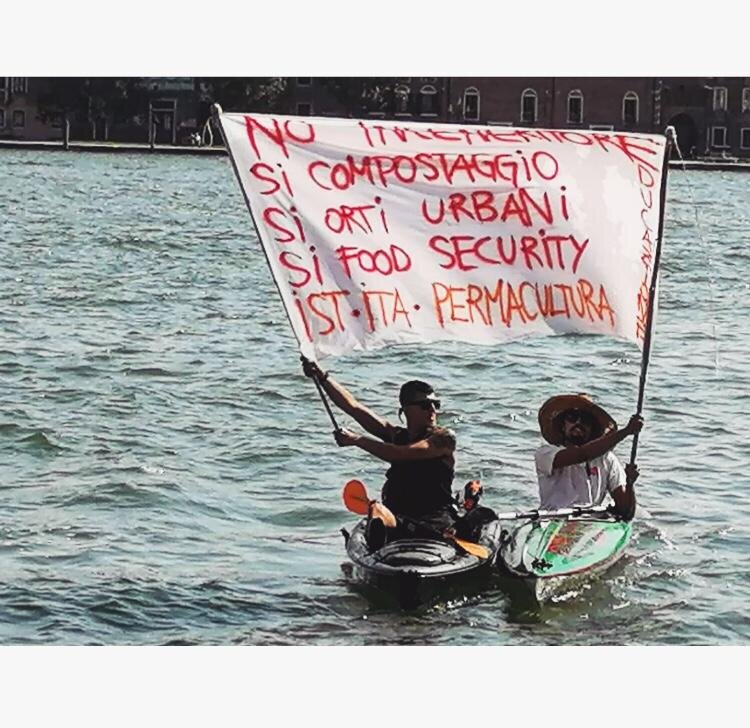

Recent protests like “Venice Fu-Turistica” have demanded new approaches to the tourist industry, including that surrounding the Venice Biennial. How much participation do tourists have in the seemingly passive, but in fact, ongoing destruction of human and other than human ecosystems? In the precarization of its workers and citizens, and the overall ruination of a sustainable life in the city? What is spectatorship when tourists only come to "see," but this watching becomes a destructive force?

During lock-down, “Venezia Fu-Turistica” demanded a reconsideration of the city’s future. However, rather than mourning the absence of tourism (and the postponement of the Biennale) in 2020, the protest questioned the current parameters of the tourist industry within Venice. Protesters are continuing to demand the implementation of urgently needed changes to the industry, that are long overdue to preserve and rebuild the long-suffering and rapidly disappearing local community. In their article "Towards Sustainable Tourism in Venice", Jan van der Borg and Antonio Paolo Russo have advocated a change of the current tourist industry in Venice, describing how the "(…) human and natural ecosystem have been modified to host the mass of tourists arriving." We have to renegotiate its terms; how will we live together?

Venice, for instance, has a precariously dis-balanced cultural scene dominated by international involvement, which has created a co-dependent local creative community based only on short-term contracts. The city has additionally gone through constant changes due to the various implications that migration, tourism, and territorial displacement have had in occasioning our current climate, social, and now health crises affecting the world, but cities alike in particular.

Questioning the current parameters of the tourist industry within Venice, "Venezia Fu-Turistica" protesters are demanding the implementation of urgently needed changes that are long overdue to preserve and rebuild the long-suffering and rapidly disappearing local community. Their demands include:

Ending the monocultural tourist industry

Limiting tourist rentals to help to regrow permanent residents

Restructuring the city as a climate justice pioneer- actively preventing economic speculators

Fighting for fair income and workers rights

Logistical support for residents and an honest tourist industry

No more large ships within the city

Finances public health, which is a common good

The city becomes feminist supporting the rights of the LGTBQ+ community

Schools, universities, and research are forges of free and critical thinking out of any logic of profit and speculation

Culture enriches people and not real estate income

The remediation and ecological reconversion of Porto Marghera are started

The cementing of the city's green areas is prevented, and property speculation stops

A new social welfare plan is re-launched

Abandoned spaces are recovered and returned to public and collective use

Focusing on public schools by investing in school construction and guaranteeing a real right to study.

With this example in mind, it is clear that we can no longer advance an institutional critique that looks at museum's content and their stakeholders without further interrogating forms of extractivism that the museum and biennials exert today towards the people that work for them, towards their surrounding communities and the natural environment. Taking the city and its larger cultural network as an example of a community's struggle, we aim towards the possibility of implementing a rewilding framework that invites the local community, the international art world, and agents beyond the human to enter into assemblages for alternative modalities to living together.

The Tourist as a Spectator

While the term "spectatorship" has been used to describe the act of watching something without taking part and has often been a site of critical inquiry within curatorial theory, we propose to think of spectatorship in the context of mass tourism, mega cultural events, and underlining exoticism. In Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, art critic Claire Bishop describes the concept as: "the audience, previously conceived as a 'viewer' or 'beholder,' is now re-positioned as a co-producer or participant." However, when considering the phenomenon of tourism as spectatorial, art spectatorship remains to be a passive term. In fact, American critic Lucy Lippard has asked pertinent questions about different tourism models where the tourist isn’t the ‘pimp,’ and the local isn’t the ‘prostitute’. How can this exchange and interaction between host and visitors be mutually beneficial, equitable, and reciprocal, especially for art visitors and museums? How can views of the landscape change our relationships as visitors and guests in a place, as opposed to owners, consumers, and mere users of these places as resources?

Venice as a commodifiable brand formed during the invention of travel for pleasure in the era of Romanticism, which was fueled by publications like "The Stones of Venice" (1851) by the English art historian John Ruskin. In it, Ruskin noted the aesthetics of the ruin took on a crucial role in the objectification of the city as a setting. The "uniqueness" of the area is thus defined by its apparent unchangeability, which creates the illusion of timelessness, evoking imaginaries of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque. Thus, the ruin-esque aesthetic only enhances the effect of a Disney-esque view whereby objects are "suspended" between past and present, life and death, destruction and creation, altogether constitute an allegorical view where the tourist enters the space as if entering a frame, or a movie.

A testament to the performativity of spectatorship in mass tourism and art tourism, in particular, is the opera-performance Sun and Sea, a collaboration between Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė. Premiering in 2017 and curated by Lucia Pietroiusti for the Lithuanian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, where it was awarded the Golden Lion.

The immersive opera presents us with an environmental commentary relating to global tourism's carbon footprint and its community impact. Without alluding to the usual anthropogenic representations of nature, the installation and opera create a ludic scenario where volunteering participants freely sunbathed and hung out as if on a real oceanscape. The calmness and naturality of the entire scene contrast with the usually crowded tourist sites and their devastation of natural environments offering a fascinating look into the issue of consumerism, human occupation, and climate change. Curator Lucia Pietroiusti’s description of the piece highlights the everyday idyll of the scenery and its underlining fragility: “Imagine a beach – you within it, or better: watching from above – the burning sun, sunscreen and bright bathing suits and sweaty palms and legs. Tired limbs sprawled lazily across a mosaic of towels. Imagine the occasional squeal of children, laughter, the sound of an ice-cream van in the distance. The musical rhythm of waves on the surf, a soothing sound (on this particular beach, not elsewhere). The crinkling of plastic bags whirling in the air, their silent floating, jellyfish-like, below the waterline. The rumble of a volcano, or an airplane, or a speedboat. Then a chorus of songs: everyday songs, songs of worry and boredom, songs of almost nothing. And below them: the slow creaking of an exhausted Earth, a gasp.”

In fact, relating to Venice’s tourist crisis, the piece offered a forceful confrontation of the local community with outside visitors speaking directly to efforts advanced by grassroots organizations such as Sale Docks who are trying to create real change vis-a-vis the impact of cruise ships while raising awareness around visitors about the detrimental effects of mass tourism. The topic of tourism is now at the center of many art conversations, especially as it pertains to the urgent need to rewild cultural institutions making them more accountable for the artistic tourism that they attract, changing the definition and behavior of “art visitors,” and actively engaging in sustainable practices across the board, which is exactly what E-WERK Luckenwalde is trying to do as one of the first fully sustainable art spaces to emerge from the environmental crisis.

Image credit: Sun_Sea (Marina), opera-performance by Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte, Lina Lapelyte at Biennale Arte 2019, Venice © @ewerklukenwalde and Andrea Avezzu, Martynas Norvaisas

The Caribbean: An Interview with Annalee Davis

In a different context but a relatable reality is the work and practice of the artist Annalee Davis. We interviewed Davis to better understand the struggle against mass tourism in Barbados and the place of art in advancing a critical view to oppose mega-developments by the tourist industry in the Caribbean.

CR: With all the signs of global environmental catastrophe and amid COVID-19, are we as a postcolonial nation asking what a future tourist economy would look like in the context of hotels emptying out? Have the decades-long warnings of global warming taught eager developers little to nothing?

AD: While the extractive practices of first-world countries are the main contributors to our environmental problems, we cannot ignore how resource strained Caribbean governments pattern their own models of development on cloth cut by our colonial histories, unceasingly threatening the human and ecological well-being of this region.

In the early nineties, I was responding to heated national debates questioning the future of a landscape caught between a sugar industry with its weighty associations with slavery, sugar production costs that were among the highest in the world, and the development of tropical islands as exoticized playgrounds for foreigners, catered to through the development of golf courses, ever grander hotels and possibly casinos. My work “The Things We Worship” (figure below) exposed contradictions that, if left to prevailing market trends, would go unchallenged.

It consisted of an altarpiece activated during a 1992 performance at the dilapidated Vaucluse sugar factory as part of a one-day ‘happening’ called Art Over Sugar. When closed, the altar displays a central image of a rural Barbadian landscape flanked on one side by a fish out of water and sugar cane at sea. On the reverse side is a line-drawing of a rural landscape tapering off to a ‘cut along the dotted line’ – eagerly followed by scissors – a reference to unscrupulous permissions granted for subdividing prime agricultural land for housing lots and golf courses, requiring the use of pesticides and copious quantities of water in an already water-scarce country.

CR: These precedents against tourism situate today’s climate emergency into a much larger view of human agency. It follows what scholars have also termed the plantationocene to contest the already accepted Anthropocene and acknowledging the role that plantations and colonialism have played in this age of human destruction.

AD: How do small island developing states revise the tourist economy so that our best resources and natural assets aren’t preserved for only those who can afford it. During COVID, the government of Barbados offered our coastline as a berthing station for cruise ships to have a ‘safe’ harbor when no other Caribbean islands would have them. Now we understand that their anchors weighing 5 tonnes with 300 meters of heavy anchor chains, swinging on the ocean bed, has caused rampant damage to thousands of square meters of our coral reefs as the chain drags back and forth in a 180-degree arc. This will take more than 100 years to rejuvenate. So while we have loyalty from cruise ship companies who want to and will ply their trade when we reopen to tourism, we have lost some of our precious reefs. Fairtrade?

How will we live together?

Annalee Davis, The Things We Worship (1992). Still from the performance at the Vaucluse Sugar Factory with Dr. Colin Hudson, St. Thomas, Barbados. Image courtesy of the artist.

Neo-Tourist Aesthetics

To address the growing effects of tourist aesthetics and architecture, we explored the works of Croatian artist Lana Stovicejic. Her practice further unpacks the long- and short-time effects of tourism on exemplary cases within the coastal landscape and cities of Croatia.

The exponential growth of new urban developments and architectural motifs conveys an unrecognizable and eclectic kitsch taste that has, in turn, influenced changes to the cultural, social, economic, and environmental fabric of Croatia. Lana Stojićević has researched contemporary neo-style tendencies in the context of illegal construction in Dalmatia through various media, approaches, and conceptual solutions. She explores and interprets the visually intrusive and almost picturesque aesthetics of unplanned constructions made for the tourist economy. Underscoring its kitsch elements and its environmental impact, the artist points out how architectural eclecticism empties the meaning of "Croatian identity" typical of the postcard scene.

The work unpacks the palimpsest of Croatian history and urban development, allowing us to ask: how can we re-inhabit the quickly transforming terrain and evermore diminishing landscape that has been in service of the tourist economy for decades?

The intermediality of her practice between photography, performance, and edibles adds a satirical and ironic twist to her work, bringing a humorous quality to a deeply political theme. Stojićević’s surrealist, imaginary language is a valuable voice within the international artistic discourse, as her practice allows us to explore crucial questions of our living reality through a playful lens. The artist has created a mesmerizing and colorful visual language that advances a critical commentary on the transformations of the landscape in a region where tourism, urban development, and “apartmentisation” are spreading uncontrollably.

Lana Stojičević's photographs direct an ambiguous and unsettling gaze towards an Adriatic coast that we normally associate with happy beach holidays. Inspired by the book “Yugoslavia’s Sunny Side: A History of Tourism and Socialism (1950s-1980s),” Stojičević proposes a link between Perković’s “Yugoslavism” or socialist modernist architecture and our contemporary global context. Facing the vistas of modern ruins, Stojićević’s awe-inspiring and semi dystopian sceneries provides a contemporary take on the role of spacing in today’s mass tourism industry, especially as she captures Croatia’s attention to what she humorously calls the “neo-ornament” to reflect on the incorporation of eclectic neo-traditional styles in architecture.

To advance a political commentary on the consequence of decades of mass tourism, Lana Stojičević becomes a tourist herself, traveling to another planet where her imaginative and beguiling environments resemble an outer-space oasis for negotiations during the former Yugoslavia and contemporary globalization.

Nominated for the prestigious Radoslav Putar art prize in 2021, Stojićević has become celebrated for a series of works that provide oblique commentary on the uncontrolled growth of vacation houses along the shore. In her 2018 series Fasada, she photographed herself wearing an outlandish pink costume made in imitation of a coastal holiday villa. It continued a theme visited in earlier projects Villa Rosa and Parcela, in which modern apartment developments were reimagined as models, toys, or cakes. The international press has already feted Stojićević for Sunny Side, an arresting series of photographs involving the futuristic swimming pool of the Hotel Zora in Primošten. Using both the real pool and models of it reconstructed to look like a flying saucer, Stojićević’s photographs suggest a sci-fi scenario that plays eloquently on the modernist aspects of the Adriatic landscape.

Alternatives: Nanotourism and Curation as Hospitality

Architects and founders of the working group AAnanotourism, Tina Gregoric, and Aljosa Dekleva, propose the term nanotourims as “an alternative that describes and criticizes the environmental, social and economic downsides of conventional tourism while taking into consideration the protection and enhancement of the local heritage, development of responsible economies and social inclusion.” They suggest a reexamination of the very meaning of the 𝘵𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘵::

“tourist is an increasingly used term that more often implies a shallow interest in the cultures or environments.” To better the systems that promote encroaching structures of mass tourism, the concept, and more importantly, the practice of nanotourism, becomes a social tool that stimulates mutual interactions and “aims to confront the current realities and presumptions on tourism. [...] Instead, Nanotourism suggests becoming a 𝘕𝘢𝘯𝘰𝘵𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘵 who drifts away from superficial one-way observation towards a participatory two-way relationship of exchange or co-creation.”

The term and notion of nanotourism were defined further by a cross-disciplinary team in the process of working theory during BIO50 - 24th Biennial of Design Ljubljana. Since 2014 the annually held AA nanotourism Visiting School program visits different locations worldwide to investigate further into nanotourism by researching, designing, and making prototypes of nanotourism experiences. Nanotourism grew into a platform of individuals and institutions collaborating on nanotourism by conducting theoretical research, finding experiences, organizing and participating in workshops, talks, exhibitions, and applying this knowledge by creating new case studies.

To best introduce the concept and practice of nanotourism we examined the impact that KSEVT - Cultural Centre of European Space Technologies has had in the small village of Vitanje in central Slovenia. An old community center building was removed to provide space for the new KSEVT building, which was designed to facilitate Space Technologies' research and honor the work of Herman Potočnik Noordung - a Slovene rocket engineer and pioneer of astronautics.

In a village of 600 inhabitants, all strongly connected to nature and the local natural heritage, the newly built center KSEVT has brought imbalance and a considerable change in their everyday life of the community given that the building brings up to 25.000 visitors per year.

AAVS has visited the site in 2014, 2015, and 2016 to mediate and find ways for creating bonds and relationships between KSVET and the community of Vitanje. Encouraging, on the one hand, the participants and residence researchers at KSVET to experience and extensively learn about ways of existence in the social and physical context of Vitanje, and on the other hand engaging with the community of Vitanje to take advantage of the new situation without losing touch with their local heritage.

With the aim of investigating and improving possible alternative ways of avoiding devastating forms of tourism, AAnanotourism is implementing critical thinking into architecture and design to better engage in locally-scaled, sustainable, and accountable “guesting”?

In line with this proposal for “guesting” brought about by AAnanotourism, Mirela Baciak, curator at steirischer herbst festival, contributed to this discussion the concept of 𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘱𝘪𝘵𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘺 as an alternative to the practices of mass tourism and we asked: “Can art visitors also become guests in that they are not careless spectators and tourists, but reciprocate in the act of care provided by the host and its larger environment?

Baciak has been researching conditions of hospitality in curatorial contexts in the past years. She proposes this fascinating take on hospitality as a way to counter conventional understandings of the art visitor and institutions’ own relationship with them.

“Hospitality is most commonly understood through its spatial dimension as a situation in which someone enters another person's space, which he or she defines as its own—most of us first experience hospitality within the realm of our own home. However, interactions that take place under hospitality may go beyond an individual's private life into spheres of social and political organization, such as institutions or even states. From the perspective of an individual, hospitality is about one's ethical relation to a stranger; the act of hospitality poses an exercise in self-othering. In this sense, hospitality is about the ability to see the other in oneself and accepting the other as s/he/they/it is.

In the context of art and its institutions, hospitality as a guiding curatorial principle has to comply with bureaucratic protocols and the economic relations defined by contracts and invitations (even when 'everyone is invited'). Since an art institution is not a home, but a place by definition open to the public where crossing the threshold between what is mine and yours is not the same as when a stranger enters one's private space.

Despite these obstacles, hospitality might be how an art institution produces and manages its ethos, boundaries, openings, and identity. The sharing of physical space might be a prerequisite for the emergence of a mental space to practice hospitality as an ethical negotiation. If this could last longer than the limited duration of a usual public program, art institutions may one day transform into something entirely different.”

This idea of hospitality, as much as that of nanotourism, is a new framework for dealing with art tourists and even the broader idea of “community” that art institutions struggle so much to define. It proposes a thought-provoking possibility for thinking more carefully about a culture of care. Building on Baciak’s definition, hospitality entails recognizing the everone's well-being, comfort, safety, and joy. In that regard, we come back to Collective Rewilding's original question: Can art Institutions becomes sites for repair and care? Can art visitors also become house guests in that they are not careless spectators and tourists but reciprocate in the act of care provided by the host and its larger environment?

Collective Rewilding in conversation with AA Nanotourism founders Tina Gregoric and Aljosa Dekleva.

In the interview we explored the question of how implementing critical thinking into design and architecture help us better engage as tourists?